Virtual Wave Tank - Generating Gravity Waves in PreonLab

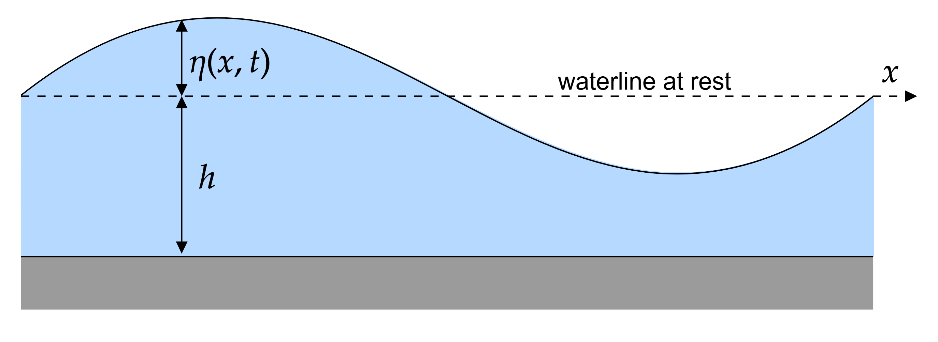

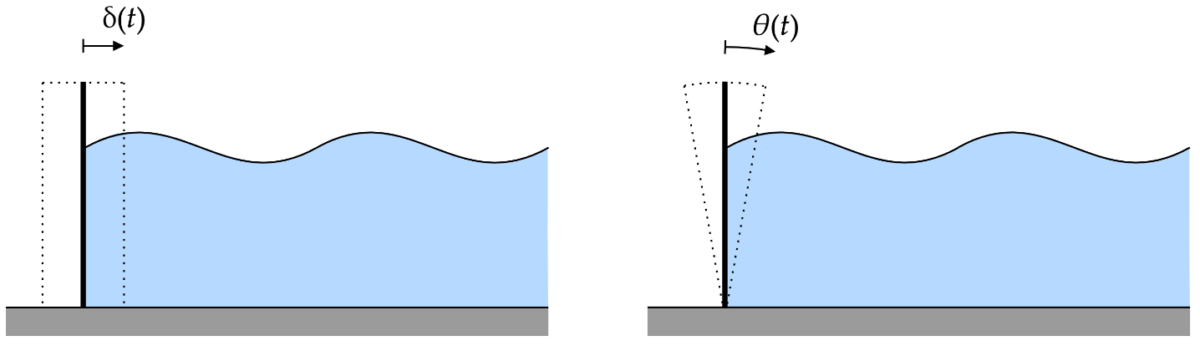

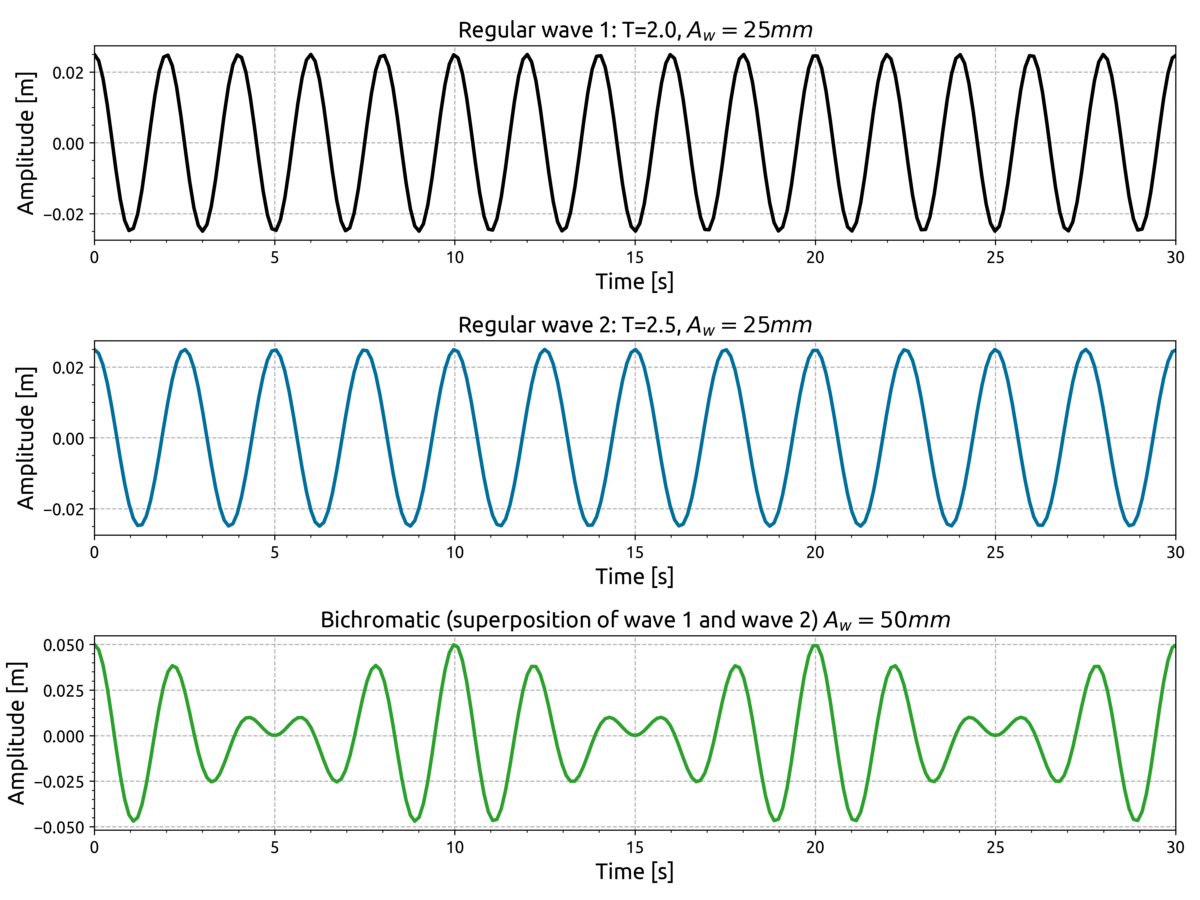

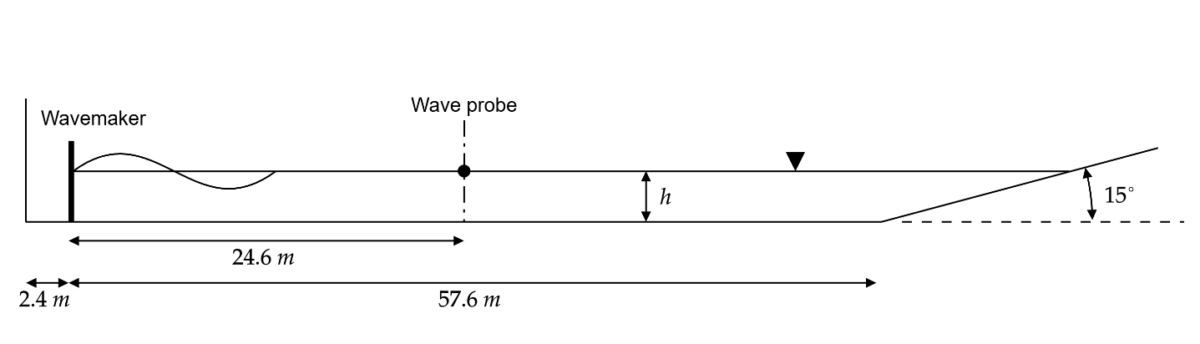

To design efficient maritime and offshore structures, a good understanding of the dynamic response to hydrodynamic loads is key. To make better design choices, hydrodynamicists historically relied on model-scale experiments. A specialized laboratory facility called a wave flume, wave basin or wave tank is used to study the behavior of water waves and their interaction with structures or sediments.

Due to the limited dimensions of wave tanks, experiments are often performed with scaled down models, leading to unwanted scaling effects. E.g., it is in practice very difficult to have parity in Froude and Reynolds numbers between model and full scale, which leads to over or underestimation of hydrodynamic forces.

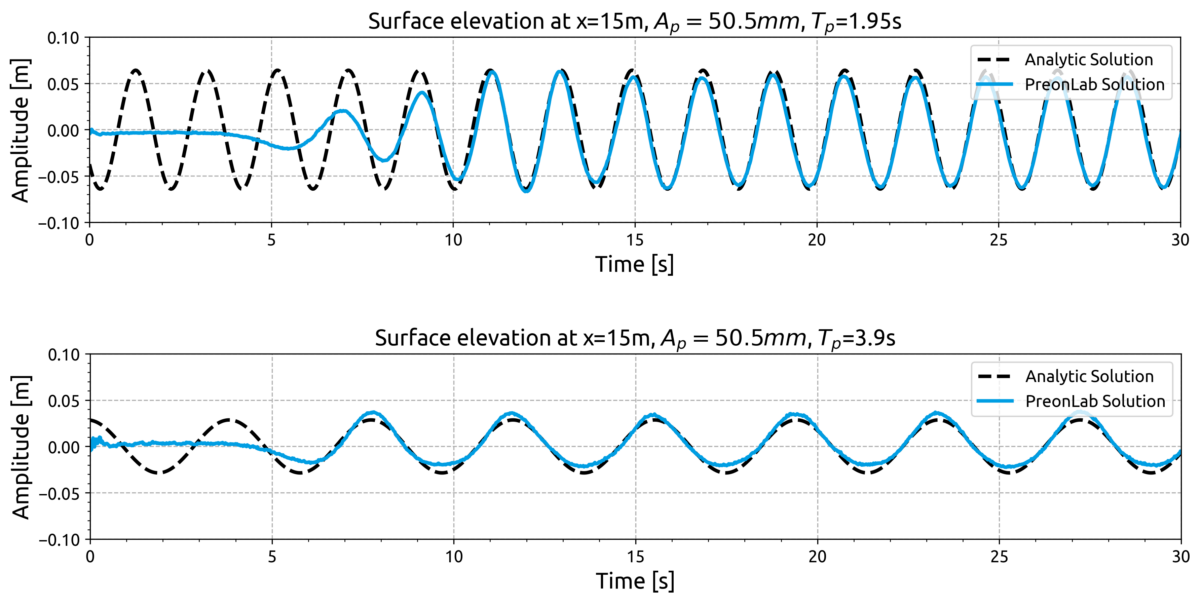

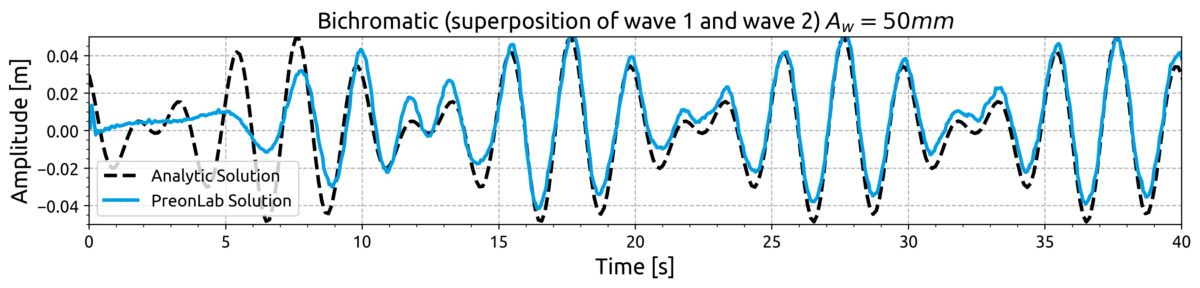

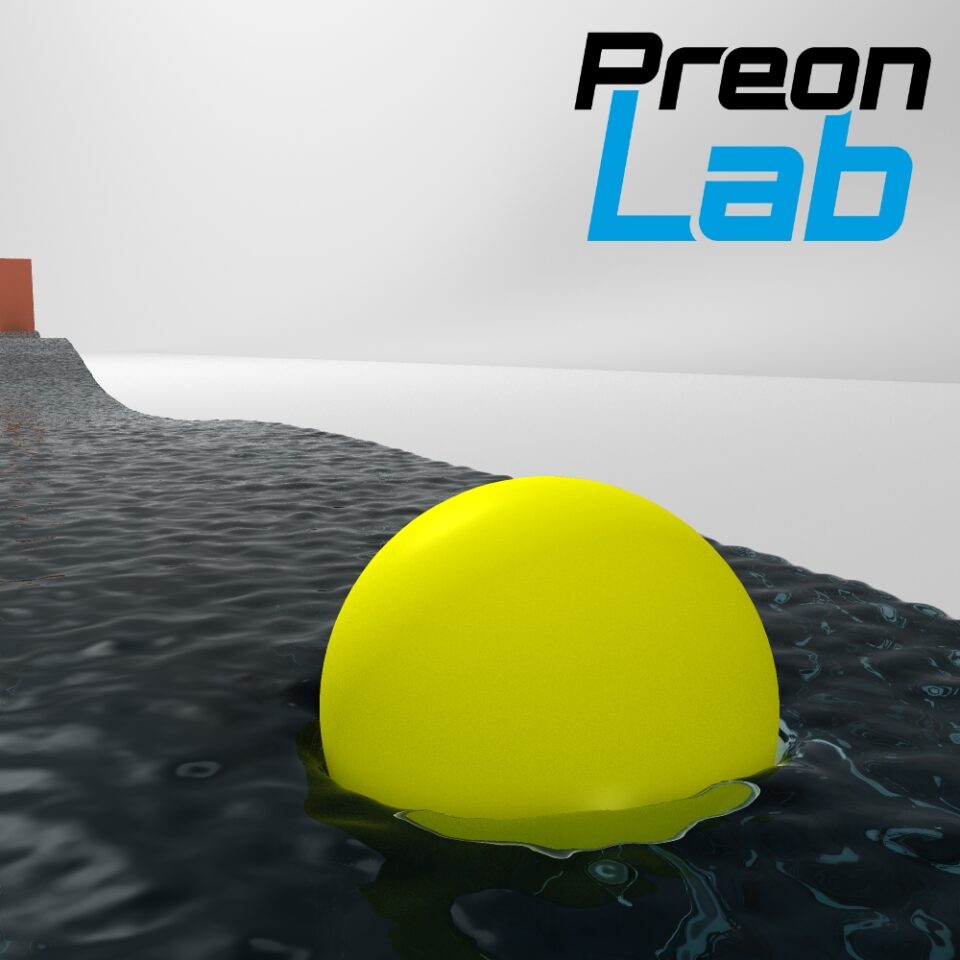

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), on the other hand, allows researchers to do full scale experiments using a numerical representation of a wave tank. In this article we will demonstrate how to simulate a numerical wave tank using PreonLab’s mesh-free approach, and convenient built-in features to model free-surface flows and rigid-body kinematics.